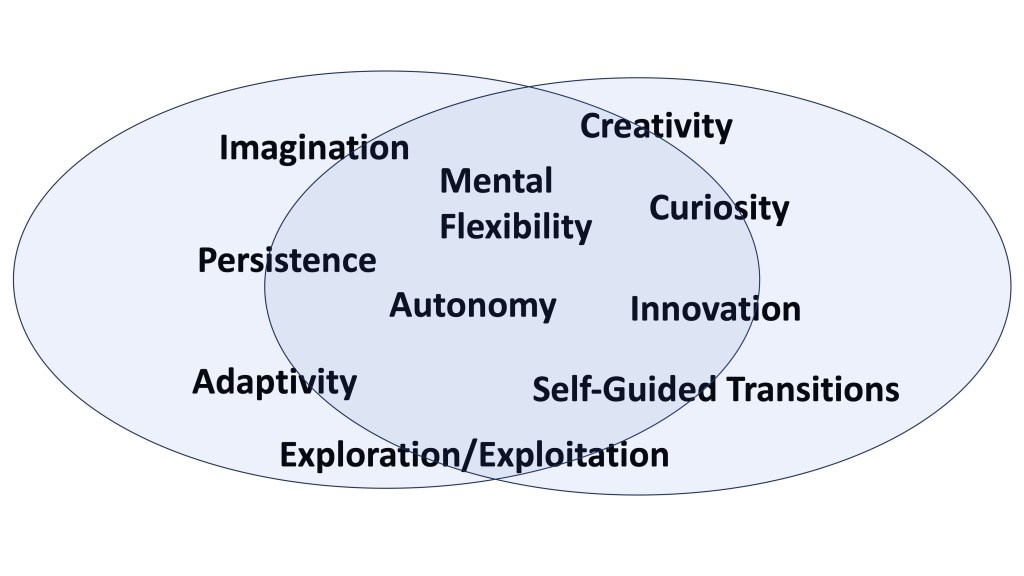

How does the human mind innovate and create using past and present knowledge? What enhances—or impairs—our ability to optimally take advantage of our acquired experience and learning? How can we best promote mental agility to creatively and adaptively meet challenges, and to make the most of opportunities across the lifespan? What cognitive, behavioral, and brain mechanisms are central to an agile mind? My lab, using the diverse and convergent methodologies of cognitive neuroscience, explores these questions focusing particularly on the role of different levels of specificity of representation in the content of our thoughts (what we might call “detail stepping”) and varying degrees of cognitive control in the processes of our thinking (“control dialing”).

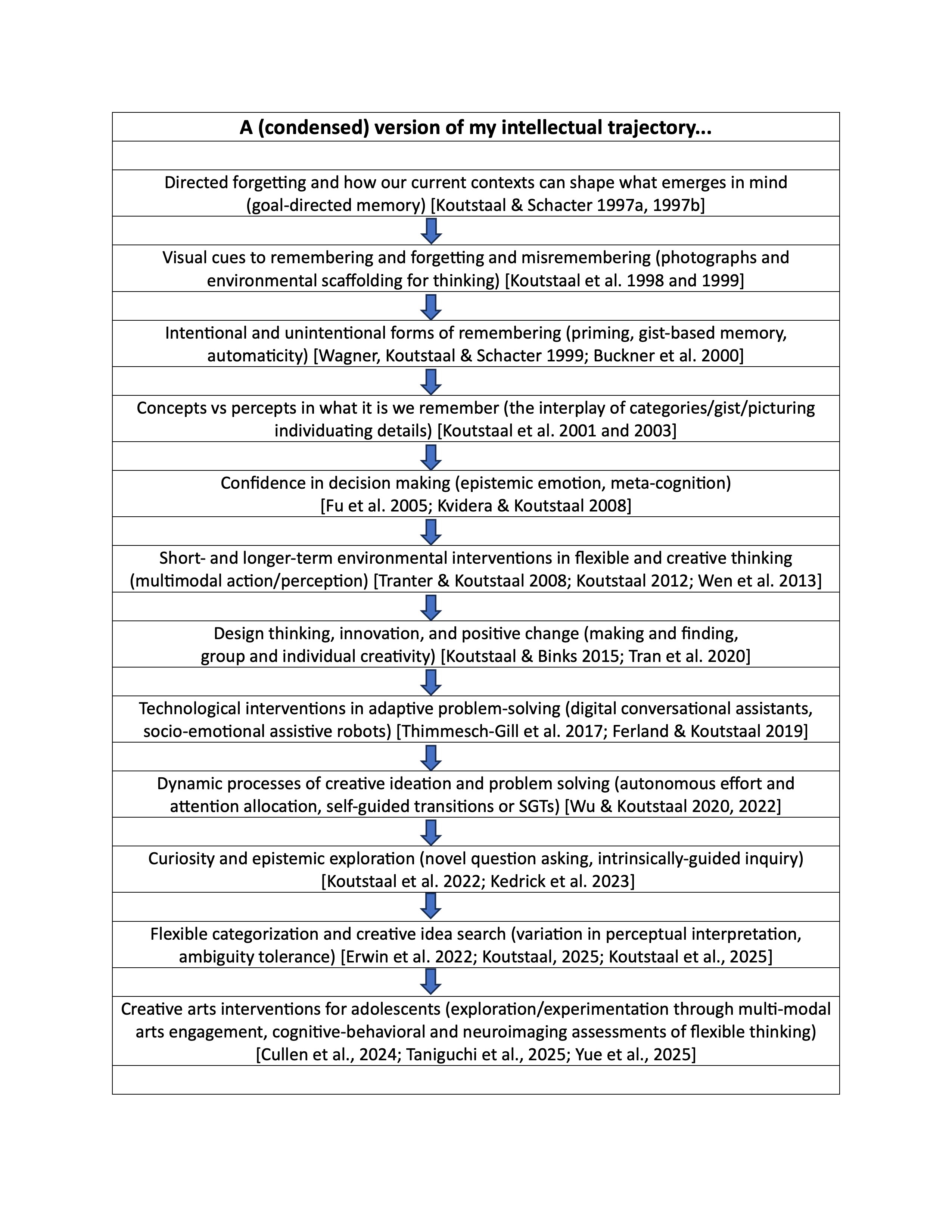

My interest in mental flexibility stems from a long-standing pursuit of the processes and mechanisms of how we intentionally use our memory, perception, and attention to reshape how we interface with problems and opportunities. From my perspective, this has meant that I’ve always resisted strictly categorizing cognition separately from motivation/goals, emotion (epistemic and otherwise), and perception. My work has aimed to introduce new ways of assessing memory and thinking, through using visual materials (both representational and non-representational) often countering a possible over-emphasis on verbal or semantically familiar stimuli. This has led to my lab and colleagues developing a number of new paradigms and assessment tools, such as: the categorized pictures paradigm, abstract and familiar object stimuli, and ambiguous shape stimuli (Figural Interpretation Quest, FIQ) along with neuroimaging-friendly measures of imagination and perception. I have developed, with colleagues, various interventions in flexible thinking in older adults, college students, and most recently in adolescents. We have demonstrated improved fluid reasoning and insight problem solving in older adults and enhanced originality of divergent ideation in college students. Effective and generative idea search requires attunement to one’s own thinking processes and goal progress (which is a blend of cognitive/emotional/motivational contributors) and is continually intersecting with our environments (social, symbolic, and physical). Flexible thinking (and openness to experience) is not just something that happens within our heads…

Some examples of current and ongoing work in our lab:

- flexible categorization and perceptual interpretation in visual/spatial creative tasks (e.g., the Figural Interpretation Quest or FIQ), see Koutstaal_Figural_Interpretation_Quest_2025

- dynamic processes of creative ideation and problem-solving assessed by Self-Guided Transitions or SGTs, see Koutstaal_2025_self-guided-transitions_and_creative_idea_search

- curiosity, question asking, and creative ideation; see Koutstaal_curiosity_creativity_connection_2022

- creative arts interventions for adolescents and assessment of cognitive, neural, and behavioral changes (collaboration with Dr. Kathryn Cullen, Dept. of Psychiatry), see Yue__Koutstaal_creative_imagination_task_adolescents_2025

- technological interventions in adaptive problem-solving, e.g., digital conversational assistants, see Ferland__Koutstaal_conversational_assistants_deliberate_positivity_2025

Why minds, brains, and environments? Consider this from my latest book, Innovating Minds: Rethinking Creativity to Inspire Change:

“Thinking emerges not just from our brains, our minds, or our environments in isolation but from an ongoing dynamic interaction of brain, mind, and environment. By gaining a better understanding of our thinking (our own and that of others across time) we can optimize our “innovating minds” — minds that continually creatively adapt themselves, flexibly building on what they have learned, helping others to do so, and shaping environments that sustain and spur further innovation.”

Available from: Amazon.com, Barnes & Noble, Oxford University Press